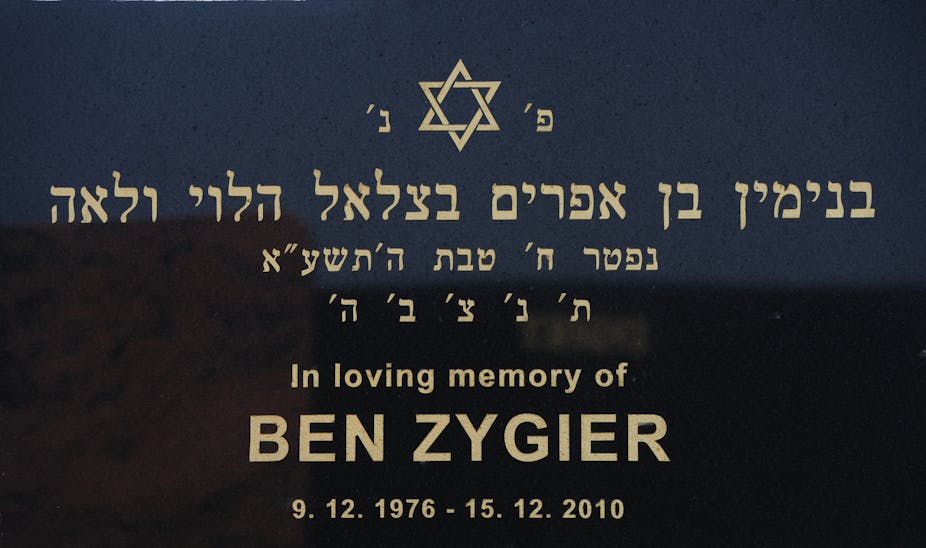

When Melbourne man Ben Zygier, an alleged agent of Mossad, or perhaps a double agent, died in December 2010, his end was barely perceptible.

He had been held anonymously in solitary confinement at a high-security prison in Israel. A notice of his death appeared on the Internet, and then promptly disappeared. His name was not made known at the time.

It had to be secured by Australian investigative journalists. Australian authorities were informed of the death, and the unfortunate man’s body was returned to his family in Australia, but leaving behind his wife and children in Israel.

Ben Zygier (also known as Ben Alon, Ben Allen and Benjamin Burroughs) was supposed to have disappeared quietly, and neither Australia nor Israel seemed in a hurry to shine any light on the incident.

Ben Zygier had been locked in the high-security Ayalon prison for ten of the eleven months after the much-publicised death of a senior Hamas figure, Mahmoud Al-Mabhouh, in Dubai on 19 January 2010. The timing is most important, as Zygier was reportedly taken into custody a month later.

Al-Mabhouh’s assassination had been organised for Israel by 26 agents of its external intelligence agency, Mossad. The majority of these had travelled on UK or other cloned European passports. Four had fake Australian passports. Their cover was blown by Dubai authorities, who relatively quickly amassed a great deal of evidence, including CCTV footage of the agents following Al-Mabhouh to his hotel room.

In the maelstrom of press coverage that followed Dubai’s revelations, the third-party countries whose passports had been counterfeited raised very vocal protests against Israel for the unconscionable use of false passports to perpetrate covert action.

Australia’s then Foreign Minister Stephen Smith, generally a taciturn politician, was in important ways quite blunt and certain in his views on the situation, emphatically stating that “no government can tolerate the abuse of its passports, especially by a foreign government”. A member of the Israeli Embassy in Canberra (presumably the resident Mossad agent) was expelled. And then silence.

The use of counterfeit passports dominated the airwaves. In the year before the Al-Mabhouh killing, there had been other Australian press investigations going on regarding the use of our passports, but at that time the focus was on dual citizens and a technically legitimate use of the passports (through name changes).

Zygier was caught in that particular net, but protested vehemently that he had nothing to do with a covert role. The question is, where did the leads that allowed our journalists to pursue the story come from? They came from our own “intelligence sources”.

What all of this suggests is that our agencies (both news and, presumably, security) had been working hard on the use of passports by dual citizens. This may have extended to breaking the cover of one such user, Zygier. Normally, such an action will not result in the measures taken against “Prisoner X”, as Zygier became known, after being detained by Shin Bet (Israel’s internal security agency). An agent whose cover has been blown becomes all but useless to the agency they work for, and, if they have been working deep in cover in hostile areas, potentially endanger themselves.

Incarceration in Ayalon Prison was not to protect Zygier, and, as it has been pointed out by authoritative commentators, the way in which he was dealt with by Israel was really quite unusual.

But equally so, one could argue, was the “hands off” approach adopted by Australian authorities in a case where an Australian citizen had been deprived of his identity, held in a maximum-security prison, investigated and tried in camera, but whose wife had known where he was, brought in an Israeli lawyer seasoned in the human rights area, and, it would seem, have urgently pressed for something to be done concerning her husband’s plight.

Did she also contact the Australian Embassy in attempting to exhaust each and every possible method of exerting pressure on the Israeli Government? Presumably that did happen, but there was a general silence about that.

In a recent Parliamentary Committee hearing, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade gave an entirely plausible explanation as to Zygier’s case and why it had not appeared on its radar: the files were being investigated by our intelligence agencies, and, presumably, not by DFAT itself. But would Zygier’s wife not have tried to deal with the Australian authorities here regarding her husband’s desperate situation? There is general silence on that question too.

We know from what the Israeli government has said that opening up this case could cause considerable embarrassment, but it did not say for whom specifically: Israel itself, or Australia.

We have also heard the conjecture that one of the reasons why Zygier found himself in such a situation was that perhaps he could no longer bear the crisis of conscience of having his morality challenged by what he was instructed to do, or alternatively what he saw done, by Mossad, and therefore blew a whistle.

These aside, there is, of course, another potential explanation, and that is that Zygier had been a double-agent, but a very well concealed one until, presumably, his name became known to journalists, and, by extension, to the general public. If this was the case, who might his other “masters” have been?

The Zygier case has been remarkable in that, even with the scant information that has emerged since the story broke, it has provided tantalising insights into intelligence agencies both here and in Israel. However, and as so often happens, clandestine agencies, and governments, have a habit of relying on deep and stubborn silence to obliterate the sensations that emerge in such cases. If it does here, we can only conclude that the Israeli and Australian governments would prefer to have the matter buried with Zygier. The reasons why remain intriguing.